- Tags:: 📚Books , ✒️SummarizedBooks, My management principles, values, and practices

- Author:: Jason Fried, David Heinemeier Hansson

- Liked:: 6

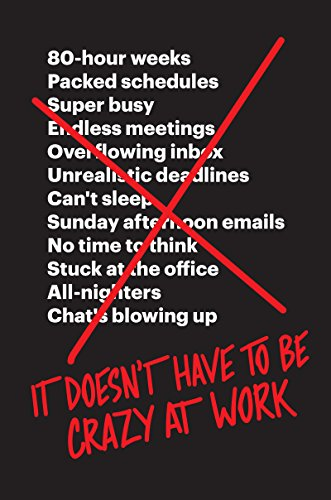

- Link:: It Doesn’t Have to Be Crazy at Work a book by Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson

- Source date:: 2018-10-02

- Finished date:: 2018-12-21

- Cover::

Like other books from Basecamp such as 📖 Remote - Office not required , it’s a book of common sense. Very hard to disagree with, and at the same time, very easy to see that for many of these things to work, you need “help from above”. Although…

You have a choice. And if you don’t have the power to make things change at the company level, find your local level. You always have the choice to change yourself and your expectations. Change the way you interact with people. Change the way you communicate. Start protecting your own time. No matter where you live in an organization, you can start making better choices. Choices that chip away at crazy and get closer to calm. (p. 224)

But why so crazy? There are two primary reasons: (1) The workday is being sliced into tiny, fleeting work moments by an onslaught of physical and virtual distractions. And (2) an unhealthy obsession with growth at any cost sets towering, unrealistic expectations that stress people out. (p. 3)

Anxiety isn’t a prerequisite for progress. (p. 6)

Curb Your Ambition

Creativity, progress and impact do not yield to brute force (p. 18)

✍️ Sin machirulos hay paraiso. Una charla heterofriendly sobre management and Cosmic Insignificance Therapy

The business world is obsessed with fighting and winning and dominating and destroying. This ethos turns business leaders into tiny Napoleons. (…) Companies that live in such a zero-sum world don’t “earn market share” from a competitor, they “conquer the market.” They don’t just serve their customers, they “capture” them. They “target” customers, employ a sales “force,” hire “head-hunters” to find new talent, pick their “battles,” and make a “killing.” This language of war writes awful stories. When you think of yourself as a military commander who has to eliminate the enemy (your competition), it’s much easier to justify dirty tricks and anything-goes morals. And the bigger the battle, the dirtier it gets. (p. 20)

Who wouldn’t want to be such a hero and a leader? But you’re not actually capturing a hill on the beach of Normandy, are you? You’re probably just trying to meet some arbitrary deadline set by those who don’t actually have to do the work. Or trying to meet some fantastical financial “stretch goal” that nobody who actually has to do the stretching would think reasonable. Whatever it takes is an iceberg. Steer clear lest it literally sink your ship. (p. 170)

No estimates

Because let’s face it: Goals are fake. (…) These made-up numbers then function as a source of unnecessary stress until they’re either achieved or abandoned. (…) Doing great, creative work is hard enough (p. 25)

Without a fixed, believable deadline, you can’t work calmly (…). Our deadlines remain fixed and fair (…) What’s variable is the scope of the problem—the work itself. But only on the downside. You can’t fix a deadline and then add more work to it (…) Another way to think about our deadlines is that they’re based on budgets, not estimates (p. 136-137)

No pain, sí gain

Pain should be temporary, no the norm (Uncomfortable enlargement over comfortable diminishment):

Sure, sometimes we stand at the threshold of a breakthrough, and taking the last few steps can be temporarily uncomfortable or, yes, even painful. But this is the exception, not the rule. Generally speaking, the notion of having to break out of something to reach the next level doesn’t jibe with us, Oftentimes it’s not breaking out, but diving in, digging deeper, staying in your rabbit hole that brings the biggest gains. Depth, not breadth, is where mastery is often found. Most of the time, if you’re uncomfortable with something, it’s because it isn’t right (…) On the contrary, if you listen to your discomfort and back off from what’s causing it, you’re more likely to find the right path (p. 34-35)

Defend Your Time

Life is about choosing

If you can’t fit everything you want to do within 40 hours per week, you need to get better at picking what to do. (p. 42)

We don’t believe in busyness at Basecamp. We believe in effectiveness. How little can we do? How much can we cut out? Instead of adding to-dos, we add to don’ts (p. 50)

Rather than put endless effort into every detail, we put lots of effort into separating what really matters from what sort of matters from what doesn’t matter at all. The act of separation should be your highest-quality endeavor. It’s easy to say “Everything has to be great,” but anyone can do that. (p. 155)

… and narrow as you go. Projects should get smaller with time, not larger.

Too much shit to do is the problem (p. 172)

Also somewhat related to Tactical tornados:

What’s worse is when management holds up certain people as having a great “work ethic” because they’re always around, always available, always working. That’s a terrible example of a work ethic and a great example of someone who’s overworked. A great work ethic isn’t about working whenever you’re called upon. It’s about doing what you say you’re going to do, putting in a fair day’s work, respecting the work, respecting the customer, respecting coworkers, not wasting time, not creating unnecessary work for other people, and not being a bottleneck. Work ethic is about being a fundamentally good person that others can count on and enjoy working with (…) So how do people get ahead if it’s not about outworking everyone else? People make it because they’re talented, they’re lucky, they’re in the right place at the right time, they know how to work with other people, they know how to sell an idea, they know what moves people, they can tell a story, they know which details matter and which don’t, they can see the big and small pictures in every situation, and they know how to do something with an opportunity. And for so many other reasons.(p. 52-52)

I wonder how this compares to 🗞 Maker’s schedule, Manager’s schedule. Is this the reason why the manager work is hard?

If you don’t own the vast majority of your own time, it’s impossible to be calm. You’ll always be stressed out, feeling robbed of the ability to actually do your job (p. 63)

Feed Your Culture

Joy Of Missing Out: JOMO

Because there’s absolutely no reason everyone needs to attempt to know everything that’s going on at our company (…). One way we push back against this at Basecamp is by writing monthly “Hearbeats”. Summaries of the work and progress that’s been done and had by a team, written by the team lead, to the entire company. All the minutiae boiled down to the essential points other would care to know. Just enough to keep someone in the loop without having to internalize dozens of details that don’t matter (p. 71)

Reasonable hours for everybody, starting for your current self

Here I fail miserably:

You can’t credibly promote the virtues of reasonable hours, plentiful rest, and a healthy lifestyle to employees if you’re doing the opposite as the boss (…). A leader who sets an example of self-sacrifice can’t help but ask self-sacrifice of others. (p. 79)

Yet people deceive themselves all the time. They think they can put in long hours for years “so I won’t have to do it later”. You may not have to do it, but you probably will do it. Because it’s a habit. (p. 148)

The boss will be the last to know, unless you ask

What the boss most needs to hear is where they and the organization are falling short. But who knows how a superior is going to take such pointed feedback? It’s a minefield, and every employee knows someone who’s been blown up for raising the wrong issue at the wrong time to the wrong boss. Why on earth would they risk their career on an empty promise of an open door? They generally won’t (…) If the boss really wants to know what’s going on, the answer is embarrassingly obvious: They have to ask! (…) Posing real, pointed questions is the only way to convey that it’s safe to provide real answers (p. 84-85)

Transparency:

If you don’t clearly communicate to everyone else why someone was let go, the people who remain at the company will come up with their own story to explain it (p. 125)

Dissect Your Process

Please, write and think

Refusing to stand on your own feet, and Writing is thinking:

When we present work, it’s almost always written up first. A complete idea in the form of a carefully composed multipage document. Illustrated, whenever possible. And then it’s posted to Basecamp, which lets everyone involved know there’s a complete idea waiting to be considered. We don’t want reactions. We don’t want first impressions. We don’t want knee-jerks. We want considered feedback. Read it over. Read it twice, three times even. Sleep on it. Take your time to gather and present your thoughts—just like the person who pitched the original idea took their time to gather and present theirs. (p. 140)

Culture is what you do

You don’t have to let something slide for long before it becomes the new normal. Culture is what culture does. Culture isn’t what you intend it to be. (p. 147).

Commitment, not consensus

Good decisions don’t so much need consensus as they need commitment (…) Companies waste an enormous amount of time and energy trying to convince everyone to agree before moving forward on something. What they’ll often get is reluctant acceptance that masks secret resentment. Instead, they should allow everyone to be heard and then turn the decision over to one person to make the final call. It’s their job to listen, consider, contemplate, and decide. (p. 153-154)

Critical thinking with “best” practices

All this isn’t to say that best practices are of no value. They’re like training wheels. When you don’t know how to keep your balance or how fast to pedal, they can be helpful to get you go-ing. But every best practice should come with a reminder to re-consider (p. 166)

3 is the magic number for a team

Nearly all product work at Basecamp is done by teams of three people. It’s our magic number. A team of three is usually composed of two programmers and one designer. And if it’s not three, it’s one or two rather than four or five. We don’t throw more people at problems, we chop problems down until they can be carried across the finish line by teams of three. (p. 174)

Mind Your Business

No “all ins”

Aligned with Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Taking a risk doesn’t have to be reckless. You’re not any bolder or braver because you put yourself or the business at needless risk. The smart bet is one where you get to play again if it doesn’t come up your way. (p. 186)

No roadmaps

Since the beginning of Basecamp, we’ve been loath to make promises about future product improvements. We’ve always wanted customers to judge the product they could buy and use today, not some imaginary version that might exist in the future. It’s why we’ve never committed to a product roadmap. It’s not because we have a secret one in the back of some smoky room we don’t want to share, but because one doesn’t actually exist. We honestly don’t know what we’ll be working on in a year, so why act like we do? (…) Promises pile up like debt, and they accrue interest, too. The longer you wait to fulfill them, the more they cost to pay off and the worse the regret. When it’s time to do the work, you realize just how expensive that yes really was.(p. 201-202)